mythologies: nadezhda alliluyeva

the tragedy of stalin's second wife viewed through the lens of mythology, folklore, and semiology.

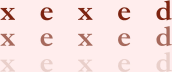

A woman reclines across a snowy landscape, breast exposed from fallen drapery and eyes downcast, as if caught on the liminal shores of waking consciousness. Her soft, womanly silhouette is belied by the marble from which she’s sculpted, and surrounded by a barrier of unbreakable glass, she will be forever frozen half-awake and half-aware of those who gaze upon her.

She is Sleeping Ariadne. As one of the most emblematic sculptures of the Hellenistic era, her figure has been oft-replicated over the centuries, dispersed through time and space. In this representation, Ariadne serves as an emblem for death—a tombstone, located in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, Russia. And, according to the caption by which it has been distributed via Tumblr, the gravesite of Nadezhda Alliluyeva, Stalin’s second wife.

Upon my discovery of this image, I was instantly intrigued, compelled not only by its aesthetic impression, but also by the underlying, simmering mystery relating to the consort of one of the most murderous political figures in history. Here exists a paradox: death and beauty and art and violence all entwined upon a mythological figure known as Mistress of the Labyrinth.

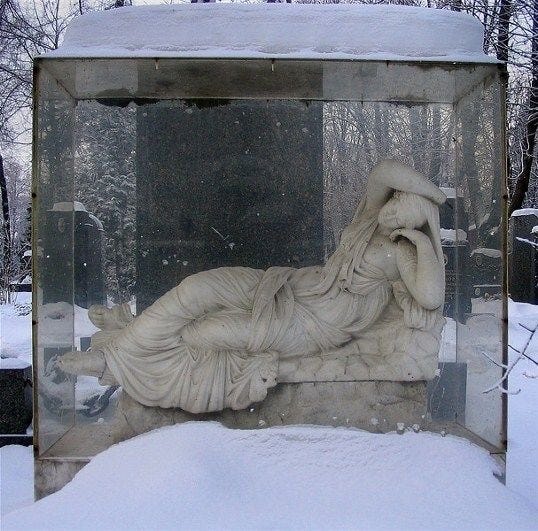

According to Greek mythology, Ariadne was the daughter of King Minos—a cruel tyrant who, every nine years, called for the sacrificial reaping of seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to the Labyrinth as food for the Minotaur.1 Minos charged Ariadne as the keeper of the Labyrinth. One year, the sacrificial party included Theseus; Ariadne fell in love with him upon first sight. She provided him with a sword and ball of thread so that he could retrace his way out from the maze after slaying the Minotaur. Their subsequent escape and elopement was derailed by Theseus’s prompt abandonment of her upon the shore. She endures a troubled sleep, captured in the sculptural motif.

The ending to this myth is varied and inconsistent, even in Antiquity. While she is ubiquitously depicted as the eventual bride to Dionysus, her mortal death is unclear. Plutarch recounts one version wherein Ariadne hanged herself post-abandonment; other versions describe her rescue from encroaching tides by Dionysus. Whether in line with the mytheme of the Hanged Nymph or Drowning Maiden, Ariadne’s associations with Nadezhda Alliluyeva are undeniably tragic.2

A child swims in the Caspian Sea. Her muscles grow weary. She begins to slip beneath the tides. Water floods her lungs. Couch, sputter, cough. A straining kick to resurface. A strangled cry for her parents, who are nowhere to be found.

And then: a hand grasps her wrist. It is so sudden, so abrupt, that she fears she may be hallucinating, dreaming, that she’s suddenly been swept under so deep that she’s entered into the half-realm of death (the troubled sleep; the liminal shores of waking consciousness). But then she is pulled to land, she is lulled to awareness, and she is met by her savior. It is a moment of confusion; she had always been taught that God is dead, after all. But then clarity strikes, as quickly as the hand that grasped her wrist: for there is no greater power than the figurehead of the State, the Bolshevik salvation of the masses.

Nadezhda Alliluyeva gazes into the eyes of her future husband, Joseph Stalin.

(This may be a fiction.)

((Her salvation from the sea by her predestined groom is alleged—a mythology that twists the paradoxical knife of her doomed fate.))

(((Your savior can become your demise.)))

((((Or reveal itself as such.))))

Their formal romance does not begin until she is sixteen.

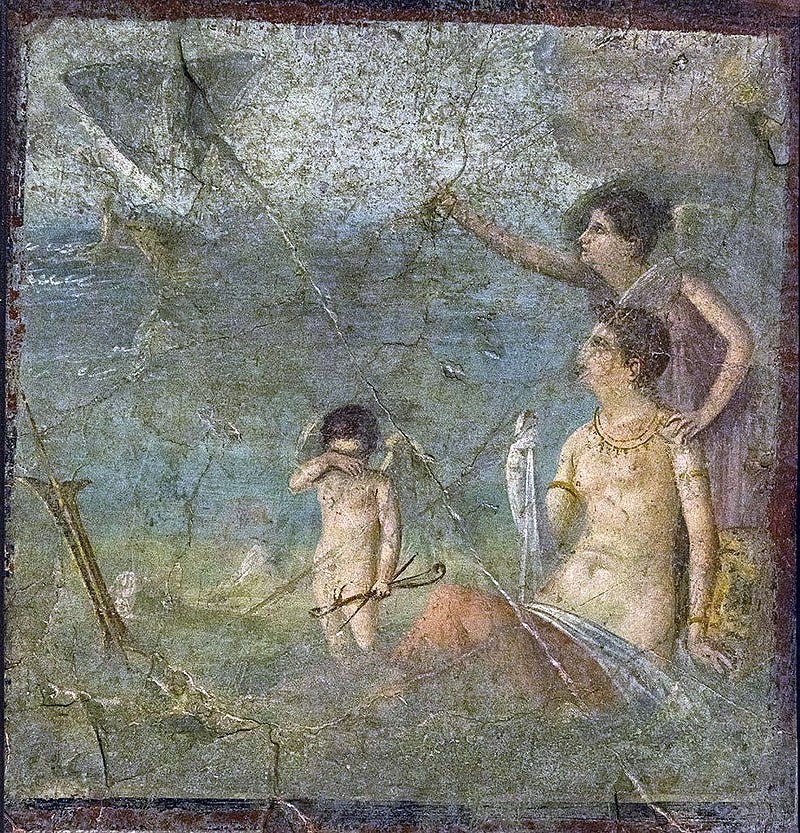

It was during the July Days of 1917 that her fated thread unraveled—a period of unrest in Russia that temporarily thwarted the growth of Bolshevik power prior to the October Revolution. Vladimir Lenin’s April Theses—a declaration that the proletariat should overthrow the bourgeoisie—had gained such traction that violence broke in the streets of Petrograd; Lenin sought solace from the destruction and found it in the Alliluyeva home. Belonging to staunch and active revolutionaries, the Alliluyevas had a long history of active involvement with the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Their ideologies were only strengthened by the honor of Lenin’s presence, and following his escape from Russia in August of that year, another prominent figure entered the picture.

(Stalin arrives.)

((Nadezhda gazes into the eyes of her savior, touches upon his flesh that had once only been the cool, intangible wisp of memory.))

(((They spend the summer drawing close to one another.)))

((((While her family feeds him, he feeds upon her.))))

They marry in the Spring of 1919.

There was no ceremony for the marriage, as Bolsheviks frowned upon religious customs. “Religion is the opium of the people,” wrote Lenin. “This saying of Marx is the cornerstone of the entire ideology of Marxism about religion. All modern religions and churches, all and of every kind of religious organizations are always considered by Marxism as the organs of bourgeois reaction, used for the protection of the exploitation and the stupefaction of the working class.” With this promulgated Death of God and aimed prevention of future implanting of religious belief (gosateizm), not only was state atheism the platonic ideal, but party figureheads became the New Lords.

Nadezhda fell in love with a man who was not a man, but rather a divinity who promised salvation to the proletariats.

(The death of a God is never bearable.)

((The fall from grace never provides a soft landing.))

During the Russian Civil War, Nadezhda and Stalin joined other Bolshevik leaders in the Amusement Palace of the Kremlin. Her husband’s involvement in the war meant he was rarely with her during this period. His fickle presence may have heightened the mythological ethos of his figure, warping him further into an Odysseus of modernity.

It appears, however, that Nadezhda was anything but a lady-in-waiting. Neglect can serve as a powerful ingredient in the brew of independence, and by the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922, her intrinsic desire for autonomy had been consolidated. The Civil War had ended, and with Stalin’s return to the home, he wanted to return to A Wife. However, not wanting to be dependent on Stalin—who had only demonstrated a poor dependability—Nadezhda joined Lenin’s secretariat, much to his displeasure. While Stalin’s annoyance likely related to her refusal of wifely duties, a green eye was perhaps cast on her move towards a greater Supreme Figure, kissing not his own boot but bowing at the helm of the Chairman.

(God is dead.)

((Who is His successor?))

Nadezhda had left school at an early age, as was custom in the Azerbaijan region. Under Lenin, she met his own wife—a woman of the same name, Nadezhda Krupskaya. Krupskaya, whose aristocratic family had descended into poverty in the late nineteenth century, had found prosperity, autonomy, and self-determination through a disciplined approach to education; as a result, she wielded strong influence over the Soviet educational system—perhaps influencing Nadezhda’s later decision to return to school. In any case, both Lenin and his cast her more kindness in her work than her husband did, forgiving spelling errors or minor indiscretions. While her lack of education set her behind her peers, her hardworking diligence was honored by the Lenins.

A stark contrast to Stalin, who frequently belittled her perceived incompetence.

(Nadezhda falls pregnant in 1921.)

((Strange, the phrasing of “falling pregnant”, as if it is an illness.))

A son: Vasily. In reign’s past, the first birth of a son is an esteem, an honor—the father, the son, and the Holy Spirit. However, in Nadezhda’s relegation from A Wife to A Mother, she was expelled from the Bolshevik Party; the reasons for this, of course, extend beyond her motherhood, as the demands of her were vast and far-reaching. In the end, it was not her husband who pushed for her reinstatement, but once again, it was Lenin who gave her the bolstering support and endorsement.

(Lenin has a stroke; the third time’s the charm.)

((His right side turns to stone.))

(((Speech loses meaning and floats in nothingness.)))

((((He falls into the troubled sleep; the liminal shores of waking consciousness; death.))))

In 1924, Stalin ascended to leader of the Soviet Union, dragging a discontent and disenchanted Nadezhda along with him. She tempered her boredom by enrolling at the academy to study engineering and synthetic fibers (Ariadne’s thread weaves a complex web). With her maiden name masking her profile, other students confided in their aggrieved opinion of Stalin’s reign, citing the Ukrainian famine and violent policies. Further disillusioned by her husband’s figure, Nadezhda confronted her husband, and his violent policies leaked into the venom of his speech—infamous arguments that rose and fell like raging waves in a storm. Another point of contention: the state of her mother’s mind, which Stalin believed to be riddled with paranoia and delusions.

(Nadezhda: “You are cheating.”)

((Stalin: “You are like your mother and believe what is not there.”))

A daughter: Svetlana, for whom Nadezhda cared very little—in line with her apathetic treatment to her now five-year-old son. Svetlana would later recall harsh scoldings and punishments from her mother as a stark contrast to the warm affections given to her by her father. Nadezhda’s livelihood was in a cool decay—a rigor mortis of the spirit.

(Ariadne dies in childbirth.)

((With Svetlana, Nadezhda transferred her joy and spirit into a new vessel; a splitting of the mind; a schizophrenic death.))

“She is like flint,” wrote Karl Pauker, head of Stalin’s personal security. “Stalin is very rough with her, but even is afraid of her sometimes. Especially when the smile disappears from her face.” In her adult diaries, Svetlana corroborated such an observation, writing that the only person her father feared was Nadezhda. The woman wielded callus detachment like the blade of a guillotine.

(She continues to crumble inwards.)

((Unborn children will not meet the same fate of a fissured mind.))

(((And so she blankly pulls seeds from her womb.)))

((((And crumbles, crumbles, crumbles inwards.))))

A series of abortions led to early onset menopause. Oscillating between the fringes of youth and decay, Nadezhda lacked the fortitude to leave her neglectful husband, and returned to him. She was only successful in leaving him when the fifteenth anniversary of the October Revolution fell with a frigid winter.

The couple attended a dinner. Her usual fashions were modest and plain—the very image of Soviet propriety. But that night, she adorned herself in silks and jewels. He drank, she drank. The storm brewed. The waves crashed.

The arguing predictably began. Stalin proposed a toast for the destruction of the Enemies of the State; Nadezhda did not raise her glass, but rather an eyebrow. Her husband threw something at her (an orange peel, a cigarette butt, a sharpened blade), and demanded her obedience.

That evening, she killed herself: from a small Mauser pistol, a bullet to the heart.

[European folklore affirms that the time of death is pre-determined. Those who commit suicide are forced to walk the earth as ghosts until the appointed time of their natural death; the place of burial is also predestined.3 Other traditions claim that one’s soul is condemned to Earth for eternity for the gluttony of depriving and devouring fate. In the case of Nadezhda Alliluyeva, her figure is now a mythology, a folktale propagated by Russian belief—and that is that great care should be taken while reading or thinking about her, or she’ll visit you in her dreams with her face covered in blood.]

According to letters written by Stalin, he was much disturbed by the event, plagued by nightmares for a period. “One death is a tragedy; one million is a statistic.” His infamous—and perhaps misattributed—quote takes on the color of soured grapes; a cruel brew of irony by Dionysus himself.

Her official cause of death: appendicitis. Staff who claimed otherwise were fired, arrested, declared as enemies to the state. It wasn’t until 1942, precisely a decade later, that her daughter Svetlana learned of the suicide.

(A betrayal akin to abandonment upon the shore.)

((Betrayal is the only truth that sticks.))

And it wasn’t until this obituary, published by the official party newspaper Pravda, that most of the Soviet Union first learned of the marriage itself. Nadezhda, once hidden and shrouded from view, was now on full display: a spectacle of death, ripe for voyeurs, as her body was placed in an open casket in the upper floor of a department store.

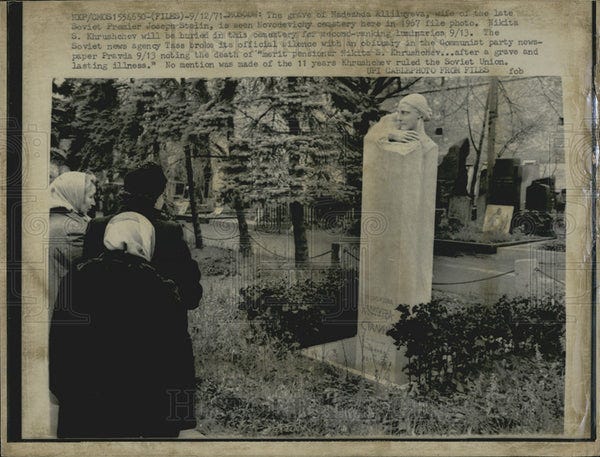

The funeral was held on November 12, attended by her family, followed by a procession to the Novodevichy cemetery. According to those in attendance, it was the only time when even the hint of tears could be witnessed in Stalin’s eyes, who repeatedly pushed Nadezhda’s coffin away and away and away, muttering insanities: How could she?!

Her coffin was lowered into the ground, and atop her final resting place, a grave was anointed: a Soviet-style bust of her profile, surrounded by unbreakable glass.

Determinably not the image that now roams the Internet’s chambers: the Sleeping Ariadne, it turns out, is a false elegy for Nadezhda’s legacy—a mytheme twisted for the Digital Age.

This misattribution, promulagated via Tumblr, can easily dovetail into a discussion of Don’t-believe-everything-you-read-on-the-Internet. I have, instead, adopted the mythology of Ariadne as a framework around my investigation of Nadezhda as an historical figure—how existence, over time, folds to imposed narratives and drowns in the variable, crashing, capricious nature of meaning and interpretation.

According to Roland Barthes, myth does not naturally occur, as there is always communicative intentions in myth. Created by people, myth can easily be changed or destroyed. By changing the context, one can change the effects of myth. At the same time, myth itself participates in the creation of an ideology. Myth doesn't seek to show or to hide the truth when creating an ideology, it seeks to deviate from the reality. “Abolish[ing] the complexity of human acts,” writes Barthes, “[myth] gives them the simplicity of essences.”

Myth removes our understanding of concepts and beliefs as created by humans. Instead, myth presents them as something natural and innocent. In this, Barthes refers to the privation of History: a History standing behind a myth gets removed. People don’t wonder where the myth comes from; they simply believe it.

I drew easy parallels between Ariadne and Nadezhda despite their lack of allegorical association. When Barthes poses the question of “What is a myth, today?” it is simply, complexly, orderly, and chaotically our endless supply to the digital Jungian cloud of created memories, inarticulate dreams, and distorted reflections.

And to who does this original gravestone of Sleeping Ariadne belong? Your guess is as good as mine; the only other recurrance of this picture appears on a site that has the indistinct aesthetics of an early Y2K blog, but cites Tumblr as its source. The grave definitely resides in the Novodevichy cemetary, along with Nadezhda’s stone figure, as verified by sorting through the tagged Instagram location. But whose body lays beneath? She is a myth forever buried, whose presence haunts the peripheries of our imaginative mind.

The Greek myth of the Labyrinth served as the original source material for The Hunger Games.

While Hanged Nymph denotes a scholarly allegory, Drowning Maiden is an invention of my own meant to dovetail into a discussion of Nadezhda.

Suggested reading: Ronald M. James, Introduction to Folklore, 2014.